Standing in a fallow cornfield next to a barren dogwood tree, an old abandoned farmhouse in southeastern Colorado appears to buckle under the weight of countless years gone by.

tin roof is falling away in strips and unruly sections, revealing the rot and corrosion eating away at the wooden base.

windows have all been shattered, and are now gaping black holes.

Time and the elements have taken a heavy toll on this agricultural dwelling, even though the words, painted on the side of its aging white frame, proclaim otherwise.

“Love is alive.”

So is faith, it seems, and hope.

Together, they meander along and criss-cross the pitted asphalt highways and dirt backroads of middle America in early December. Like destination points on a roadmap, they abide in the souls of average people, some of whom are still feeling the sting of COVID-19 in 2021—but carry on they must.

“I don’t mean to sound preachy, but it says [in the Bible] not to fear,” Kansas resident Sharon LaRue said. “I try not to be afraid.”

LaRue and her husband, Gary, are co-owners of the El Rancho Motel in rural Elkhart (population 1,888). couple purchased the motel in 2005, applying their own personal flair for down-home hospitality throughout its renovation.

In early 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic hit so many businesses across the state and nation, said LaRue, a petite woman with kind eyes and a gentle smile.

“In the beginning, I was scared to death because of all the media,” she said. “People gave me cash. I was soaking it in Lysol so you could use it. I was using gloves with every customer. I was washing door handles, windows, using air freshener and hand sanitizer—everything.”

Although the couple lost customers during the pandemic, they persevered nonetheless.

Now they’re recovering—even thriving—in 2021, while going into 2022 with a renewed sense of hope and optimism.

“It feels so good to feel good again. Hard times humble you,” LaRue said.

“As far as the [COVID-19] shot goes, I’m very negative about it, because I’ve heard of so much that’s in it. I’m against it totally.

“I’m extremely upset with the government. I have no confidence in the government. I think they’re lying, lying, lying. I think they will go down as the worst government in history.”

Her personal life is another matter.

“I’ll take it as it comes and stay close to my Creator. I’ll just take it one day at a time, though it’s easier said than done,” she said.

In the little town of Springfield, Colorado (population 1,451), Wayne Thompson and his wife, Joyce, are out enjoying a brisk Monday morning walk in the cold air on their way to a convenience store.

Wayne’s claim to fame: “I’m the only Wayne in town. That’s how small the town is,” he said.

His other claim to notoriety is that he writes copy for Page 3 of the Plainsman Herald, a community newspaper with a big mission and heart.

He’s proud of that fact—being able to contribute to its pages at the age of 75—and to build upon that community journalism spirit as a native Pennsylvanian.

“It’s a close community. I think people are closer here,” said Thompson, who feels he is fortunate not to have lost any close friends to COVID-19.

“One problem I see—and you can take it for what it’s worth—is with the television. It’s the communications and the programming. commercials—they’re garbage now. ‘Gunsmoke’—if it’s on [television], it’s worth watching it again.”

Thompson’s advice for 2022: Don’t ever lose hope.

“re’s always hope. If you have life, there’s hope,” he said.

Across the frozen plains and open rangelands of Oklahoma, the telephone poles form an endless procession as our car heads into Boise City (population 1,266), nestled within the state’s panhandle.

It’s nearly dusk, and the silvery downtown streetlights seem to outnumber the local shops and businesses five to one. Farmhouse Restaurant is open and ready to serve.

“How’s life? re’s been some COVID, some deaths from it. You’ve got to understand, they weren’t youngsters. y had underlying health issues,” said Tonya, the restaurant’s assistant manager. Because it’s a small, close-knit town, “everybody knows everybody.”

In March 2020, the restaurant went to carry-out service during the pandemic. It even closed for a while, then reopened in September 2021.

“You’ll find out here that we just kind of keep going,” said Tonya, who’s a mother of twin 13-year-old boys, as she pours a guest a cup of hot coffee.

“re are things we can’t get out here” due to supply chain issues, she said. “One time, we couldn’t get bacon. Milk is a thing we’ve had challenges with at times.”

thing about fear, she said, is that it doesn’t help when facing down the coronavirus.

“I’m not going to quit living because of something called COVID. God’s bigger than a virus,” she said.

About 260 miles south of Boise City lies Santa Fe, the capital of New Mexico, a colorful tapestry of adobe-style buildings and Spanish mission and modern architectural influences.

In the central plaza, a crowd of visitors listens and claps to the gentle strains of trumpets and guitars played by a live mariachi band.

holiday lights that are strung among the trees then begin flickering on in a dazzling display of red, blue, and white, like turning a kaleidoscope.

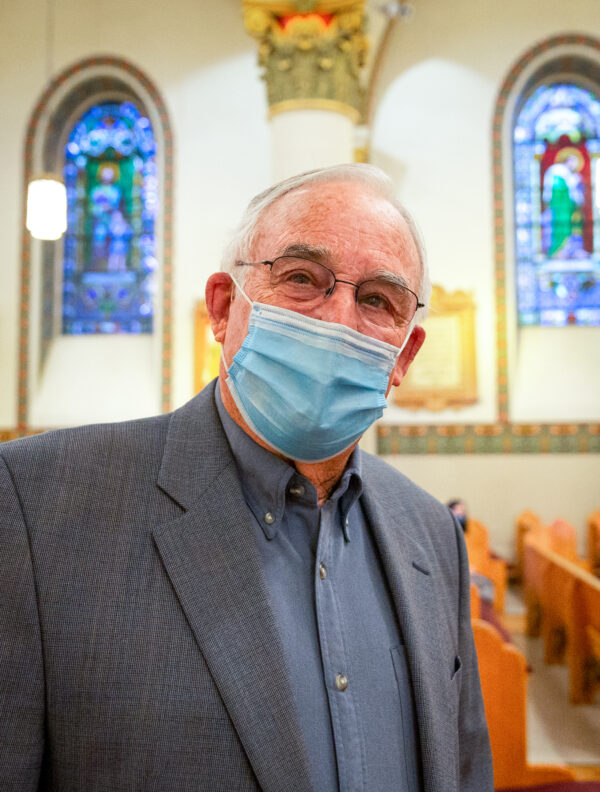

Across from the plaza, flanked by tall pines, is the Cathedral Basilica of St. Francis of Assisi, whose doors are open to anyone who wishes to enter and pray within its sacred confines of soaring columns and radiant stained glass windows.

Faith is a powerful, enduring thing, observed Thomas van Kampen, a parishioner for 18 years, from Santa Fe. “But you can’t just have faith things are going to resolve themselves,” he said.

“You just can’t say, ‘Oh, dear God, solve this,’ and not do anything yourself. Faith is manifested in what you do.”

In 2021, van Kampen’s greatest challenge was the inability to visit his three children because of the coronavirus restrictions in place.

For 2022, he prays there will be a true resolution of the bitter political feelings that have been dividing America.

“I wish I had the answer to that,” he said. “Wouldn’t it be nice if we had resolution? I think resolution is coming together. If there is going to be resolution, we have to create dialog with one another—together.”

For Shawn Surls, 34, life for him and his girlfriend in 2021 has been hard, living on the road in their 1994 Chevy G20 van.

Now it’s a matter of holding on, holding their own, and keeping the gas tank full and the money flowing in—in any way they can.

“She likes [traveling]—for now. We’re trying to find someplace we like,” Surls said while standing at the main entrance of a Walmart outside Amarillo, Texas.

Surls managed a broad smile as he held up a sign that read “Trying 2 Get Home Please Help,” his back stiff against the setting sun and cold wind blowing in from the west.

“When COVID hit, we lost our jobs,” Surls, a native Alaskan, said. “We sold our house and started traveling. I do this when we’re broke. It doesn’t take us too long to get money.”

In West Virginia, the couple suffered even greater misfortune when their van was broken into and all their money was stolen.

y decided to live in North Carolina for a while before continuing their journey west.

Colorado seems like a nice place to settle down and start again—just maybe, Surls said.

“Living on the road is not what you would think,” he said. “Most of the people we’ve met have been great. A few bad apples. It’s been an adventure. No final destination—not yet.”

For now, it’s just a matter of “knuckling down for a while.”

“You just hang in there. It will get better,” Surls said confidently.

Nearly 550 miles west, in Winslow, Arizona, Kelly Rada is setting up the lunch menu sign outside the Olde Town Grill situated along historic Route 66.

city became well-known from the Eagles’ song “Take It Easy.” And standing at the corner of Kinsley and East 2nd Street in Winslow is a bronze statue of late Eagles singer-songwriter Glenn Frey.

On Oct. 7, 2021, Rada and her husband, Paul, purchased the former post office building situated near that very corner, and they opened the Olde Town Grill, in a soft COVID economy.

“Things are going good. We’ve got customers. Everything is coming together,” Rada said. “We built all the walls out. re was a drop ceiling in here. We replaced that” with an ornate copper ceiling.

“Paul said, ‘How do you want to design this?’ What I told him is that I wanted this place to be calming. We wanted a sense of relief. I don’t care who you are or what your life is like. You are respected as a human being. Hopefully, that’s what we portray here.”

Most of all, “we liked a challenge,” Rada said. “One of my sayings in life is, ‘Life begins at the end of your comfort zone.’ Win, lose, or draw, I try to keep a happy medium.”

Though 2021 has been challenging in other ways, she said.

“My cousin passed away from COVID,” Rada said. “re have been different people who were sick, who recovered.”

One then notices the mask wrapped around Rada’s wrist. “I carry this around for safety, just for customers. We keep very well spaced,” she said.

On the other side of town, Richard Frei and Daniel Mazon, owner of the Authentic Indian Arts Store on Hipkoe Drive in Winslow, were busy talking about politics and the economy inside the store.

“Sucks. Thank Joe Biden,” Frei said. “I’m struggling. It hurts. Everything has gone up [in price], and it hasn’t let up.

“We’ve got to get rid of this administration. We’ve got to get back on track. If we don’t get rid of this administration, we’re going to be more communist than communist China.”

Mazon, who opened the store in 1972, reflected on the handling of COVID-19 by the local government, which resulted in him being placed in handcuffs, then slapped with a citation for keeping the store open during lockdown.

He said many of the items he was selling in the store were just as “essential” as those for sale at the Walmart across the street.

“I am an essential business, and they were taking that away,” said Mazon, whose grant-great grandfather was Chief Manuelito, one of the principal leaders of the Dine people during the tragic Long Walk period in American history.

“Most of the government is very corrupt,” he said. “ devil is involved. We as a nation have to turn back to God.”

Through his faith and practice as a Christian minister, Mazon said, he finds both purpose and direction—and a way to salvation through these modern times.

Holding out his hands, he invited everyone inside the store to join him in prayer.

“Don’t ever give up on yourself,” he told the guests. “Try to do the best you can. Even if you fall short, you get back up.

“Amen,” a visitor said.

Pezou : Rural Americans Speak of Hope and Optimism Going Into 2022