A Maine school board lost a battle against a parent fighting the introduction of obscene materials into schools—and has been ordered to pay him $40,000.

But Shawn McBreairty said, “I’m not taking a penny. It’s all about the win. It’s not about the money.”

In October 2021, McBreairty started a campaign to expose the radical gender curriculum in Maine’s Regional School Unit (RSU) 22, saying it promoted obscene books, glorified gender transition, and advocated radical sexual practices.

After McBreairty spoke up at his own school in Cumberland on behalf of his twin daughters, a cascade of parents contacted him to ask him to speak on their behalf, he said. His daughters have now graduated.

A pro-LGBT display in a school in Brewer, Maine, in February, 2022. (Shawn McBreairty, the Maine First Project and Maine Source Of Truth)

A pro-LGBT display in a school in Brewer, Maine, in February, 2022. (Shawn McBreairty, the Maine First Project and Maine Source Of Truth)

“People are afraid to speak,” he said. “They saw me speak out for my twins in Cumberland and they said, ‘hey do you know how bad the school is here?’”

As part of his roles as an advocate with the Maine First Project and host of the Maine Source of Truth podcast, McBreairty spoke at school meetings. He wrote about schools promoting sexual-identity exploration to children, and he publicized pornographic descriptions within RSU 22’s books.

“I was exposing what the school board chair said, which is basically that pornography is OK in the context of a book,” he said.

At a school board meeting, McBreairty read aloud an excerpt from “All Boys Aren’t Blue,” a book found in Maine school libraries.

The book describes a detailed sex scene between two young boys. The boys are cousins.

The room stopped, McBreairty said.

“They were basically shocked. They couldn’t believe what they heard,” he said. “I said, ‘if you’re under 18, plug your ears.”

In response to McBreairty’s work, RSU 22 punished him by banning him from attending school functions on campus, he said.

An LGBT book display in Hermon High School in Hermon, Maine in November, 2021. (Shawn McBreairty, the Maine First Project and Maine Source Of Truth)

An LGBT book display in Hermon High School in Hermon, Maine in November, 2021. (Shawn McBreairty, the Maine First Project and Maine Source Of Truth)

At first, the school asked him to leave campus at a meeting. Then it sent him a letter from a lawyer saying he was banned from campus for using obscenities, he said.

“I could not attend any community functions, I could not attend school meetings that I paid taxes for. Even a fair,” he said.

“They threw me out of a school board meeting,” McBreairty said.

A police officer brought by the school threatened him with arrest, he said.

On Aug. 30, McBreairty won a lawsuit against the district.

The court ordered the district to pay him $40,000 for violating his rights as a citizen.

McBreairty said he won’t take the district’s money.

He will, however, pay his legal fees with some, and use the remainder to help parents fight back against schools and assist with their legal fees.

Written Pornography

Parents across the country have launched similar battles after discovering books with shocking content in school libraries.

The radical books found in Maine schools are in other schools too, McBreairty said. Some books normalize switching a name for gender reasons to kindergartners.

“In my heart, I’ve always known that I’m a girl Teddy, not a boy Teddy. I wish my name was Tilly,” a transgender teddy bear named Thomas tells kindergartners in the book “Introducing Teddy: A gentle story about gender and friendship.”

Other books offer pornographic descriptions of sex to middle schoolers—along with illustrations.

Most schools start teaching sexual education in 5th or 6th Grade, but these books can find kids long before then.

According to the American Library Association, the books that parents most often attempt to ban include, “Gender Queer,” by Maia Kobabe; “Lawn Boy,” by Jonathan Evison; “All Boys Aren’t Blue,” by George Johnson; “Out of Darkness,” by Ashley Hope Perez; “The Hate U Give,” by Angie Thomas; “The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian,” by Sherman Alexie; “Me and Earl and the Dying Girl,” by Jesse Andrews; “The Bluest Eye,” by Toni Morrison; “This Book Is Gay,” by Juno Dawson; and “Beyond Magenta,” by Susan Kuklin.

The books include graphic descriptions of sex, masturbation, or children having sex.

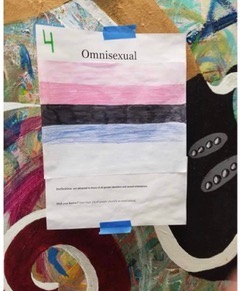

A new sexual orientation poster in Winthrop, Maine, in January, 2022. (Shawn McBreairty, the Maine First Project and Maine Source Of Truth)

A new sexual orientation poster in Winthrop, Maine, in January, 2022. (Shawn McBreairty, the Maine First Project and Maine Source Of Truth)

“All books should be in the library. All books. This is America, we don’t ban books,” said First Lady Jill Biden, the wife of President Joe Biden, in an interview about parental opposition to explicit books.

People can buy obscene books for children to read on Amazon, McBreairty said. But, he says, the books shouldn’t be in taxpayer-funded school libraries.

“Pornography is pornography. I don’t care if it’s one word, one picture, one line, whatever. That does not belong in the library for kids under 18.”

The Real Problem

But inappropriately sexual books are just smoke from the school system’s fire, McBreairty said.

“If you’re a teacher, and you put a rainbow in your classroom, you have to know what you’re doing. I don’t care if they’re kindergarteners or seniors in high school,” he said.

Teachers, curriculum, posters, stickers, school assemblies, school-led celebrations, and other school actions all push radical new sexual identities on children, McBreairty said.

Some Maine children say schools pressure them to be LGBT.

“I talked to a dad today, a father whose kid saw that the teacher filled in her pronouns on her worksheet,” McBreairty said.

Parents don’t have enough power over children’s education, he said. As a result, teachers can expose children to inappropriate materials.

Even if laws kept children safe from obscene books, unsupervised classroom teachers still have immense power over a child’s environment, said McBreairty.

“We’ve been asleep at the wheel for the last decade or two, thinking that when we drop our kids off to school, it’s just like when we went to school. And it’s not.”