After many raucous debates at Florida school board meetings, county bodies across the state have moved to make changes to their public comment policy.

Traditionally, school boards and local governments set rules and policies to aid in governing the public’s participation at their meetings. y help keep the proceedings moving along, offer time for residents to voice complaints, or concerns, and maintain civility.

However, recent threats against teachers and education officials have many school systems changing policy in order to keep their staff and board members safe.

proposed changes vary between boards but, in essence, they seek to limit the amount of time people can speak.

Boards want to cut minutes from each speaker, and even how long public comment sessions can be.

Jane Goodwin, the new chairwoman for Sarasota County School Board, revised its policy and the changes have been approved for advertisement during a workshop meeting on Dec. 7.

Sarasota’s policy would reduce public comment time from three minutes to two minutes per speaker, allow one-hour for public comment, announce their name and any group affiliation, and move public comment on non-agenda items to the end of the meeting.

During the workshop Goodwin, along with past chairwoman Shirley Brown and Tom Edwards, supported the changes, citing that “many members of the public were deterred from attending board meetings over the last year because of disruptive behavior.”

Other members, Bridget Ziegler and Karen Rose, opposed the changes because they would “limit public input and further divide the community.”

This issue is not isolated to Florida.

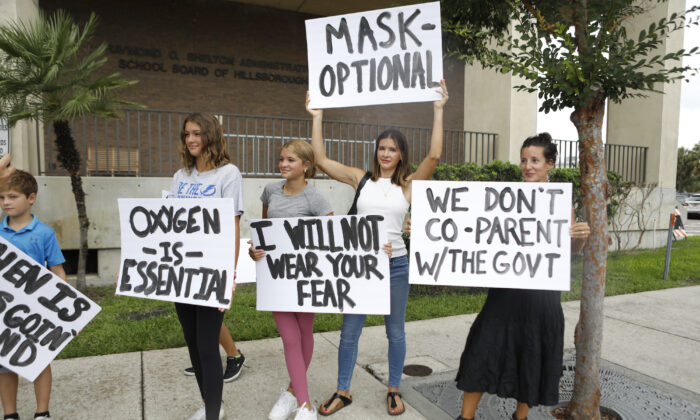

School boards nationwide are beginning to “eye ways” to “rein in” public comments at local meetings in an effort to calm crowds over hot-button issues such as critical race theory and mask mandates.

In other media reports, one Kentucky school board changed its policy so that comments be directed via email—after a meeting devolved into a shouting match.

In northern Virginia, school board officials restricted who they wanted to speak at their meetings because of similar issues.

In recent months, parents have let their voices and opinions be heard and expressed they want more control over what their children are learning in school.

Other Florida counties—such as Brevard, Orange, and now Sarasota—are looking at ideas to limit public comment as a way to, what Sarasota’s Ziegler phrased, “lower the temperature” at controversial meetings.

In Brevard County, the board is proposing changes to prevent speakers from raising signs, limit the number of speakers allowed to speak, and time limits,—especially when a large number of people are scheduled to give their opinions.

In Alachua County, audience members at school board meetings are told not to clap, or cheer, in response to speakers’ comments, or hold signs.

official policy on public participation limits individual comments to three minutes, calling up speakers in the order in which they were received on a speaker sign-up sheet at the door.

rule says the time for public comment will be 30 minutes, unless the board votes to extend the time. presiding officer may extend the time for speakers, the rule states. re’s no rule for shortening that time.

People who want to speak—and don’t get a chance during the 30 minutes set aside for public comment—“may address the board at the end of the meeting,” the rule says.

Regular attenders say that since September, the board often has restricted people to no more than two minutes of speaking.

And the time for public comment has been reduced recently to just 15 minutes, they say.

At a Sept. 7 meeting, the only person signed up to speak was Antoinette Chanel, the parent of two children in district schools.

After after making her way to the podium, Chanel told board members that two weeks earlier, she and her 8-year-old daughter were riding bicycles to her child’s school.

As they approached an intersection and prepared to cross, “I heard the diesel roar of a yellow school bus,” she said.

“I had to act quickly to keep my child from accelerating into the street to cross, because this would have placed her in the direct path of the school bus.”

bus was traveling the wrong way down a lane of traffic, apparently in an attempt to bypass a traffic jam, she said. And now her child “now wants to know why it’s ok for the school bus driver to break traffic laws.

“She said, ‘See Mom, this is why I’m scared to walk to school by myself in the morning!’

“Storytelling is my craft,” Chanel said. “But I refuse to use my precious craft to make up a story to explain away your negligence.”

She added that she had made up stories to explain the “why a police officer would kneel on a man’s neck,” and why people are “angry about wearing masks,” and why people “fly Confederate flags when the Confederacy lost.”

As the timer signaled that her two minutes to speak had expired, then-Chairwoman Leanetta McNealy tried to interrupt her.

“Oh, I’m not stopping!” Chanel said.

McNealy signaled two deputies to remove Chanel from the meeting.

“What are you going to do?” Chanel demanded.

“Escort you out, ma’am,” one replied.

“What are you going to do?” Chanel shouted at McNealy, as deputies urged her to leave.

“I came for answers! I had to hire a babysitter to watch my children so I could be at this meeting, and you printed the wrong address on the agenda! I need answers!”

As deputies urged her to leave, Chanel turned, muttering, and stormed out, shouting behind her, “I’m not done! And you are not allowed to place my life, or my children’s lives, in danger by empowering reckless people!”

But, since then, speakers have been limited to two minutes, regular attenders say.

“Speakers typically have two to three minutes to speak,” Jackie Johnson, public information officer for Alachua County Public Schools, wrote in an email.

“ board discourages statements that are abusive, obscene, disorderly, disruptive, or include a personal attack on a staff member, or anyone else.

“We ask that speakers follow our civility policy, which gives district personnel, including the board, the authority to ask someone who uses obscenities—or speaks in a ‘demanding, loud, insulting and/or demeaning manner’—to leave, or be removed from, the premises. That is also true for anyone who is disruptive or threatening.”

At the time of publication, Johnson had not responded to requests for more information about the incident and the apparent change of policy.

In early October, State Rep. Randy Fine, a Republican, filed a criminal complaint against Brevard’s board.

Fine claimed it violated Florida’s “Sunshine Laws” (open government laws) when, in September, the board chair cleared a public meeting that had “turned rowdy” and then did not allow them back inside.

Fine said the board is made up of “tinpot dictators”, who are afraid to face the public over their decisions.

Brevard was one of 11 school boards that defied Gov. Ron DeSantis’s administration rules on mandating students and staff to wear face masks.

In Orange County, the board had suggested time limits in October—three minutes for topics with fewer than 20 speakers, two minutes for fewer than 30, and one minute when more than 40 people were to speak.

board considered a “priority system” that would place students, parents of students, and employees of Orange County Public Schools first to speak, and local residents and visitors next.

Added to that would be to bar the use of video, or audio, clips—as well as banners, or flags—and prohibit people from gathering in the back of the school board chambers.

Michael Ollendorff, media relations manager for the county’s public schools, said no revisions to the policy have been made since Dec. 16, 2016, but would not say if the measure would be addressed in upcoming meetings.

Sarasota’s Zeigler said that criticism over decisions the board makes “comes with public office”, and added as a 7-year board member she took an oath to “hear from the public.”

She also said that the way that parents have been treated at board meetings have “unforeseen consequences.”

“Some parents, when speaking at board meetings, have been met with a level of disdain,” she told National Public Radio on Oct. 19, 2021.

“People have a right to petition their government, and when you try to muzzle, or limit, the public’s right to petition government it further fuels frustration.”

contentious school board meetings that have garnered national media attention caught the attention of the White House, where the FBI was called upon to monitor parents who voiced their concerns to the point they could potentially be labeled domestic terrorists.

This has not sat well with Florida Governor Ron DeSantis as he weighed in on the subject at a press conference in October.

“To mobilize the FBI, there’s no need for it,” DeSantis told reporters. “ reason to do that is to intimidate parents, to squelch dissent, to have them shut up and just take it—even when they strongly disagree with what may be happening to their kid.”

Sarasota School Board will continue the discussion in January and will vote on the new policy in February.

Pezou : Florida School Boards to Lessen Time for Parents to Speak