Hollywood tends to ruin its remakes of classic movies with clumsy attempts to update them and make them “relevant.” Two examples are the cheesy 1976 “King Kong” and Amazon’s current desecration of “Cinderella.” So, like many others, I cringed when I heard that Steven Spielberg was filming a new “West Side Story.” 1961 original is a national treasure. How many ways would they find to mess it up? Before answering that question, here’s some background.

Making of ‘West Side Story’

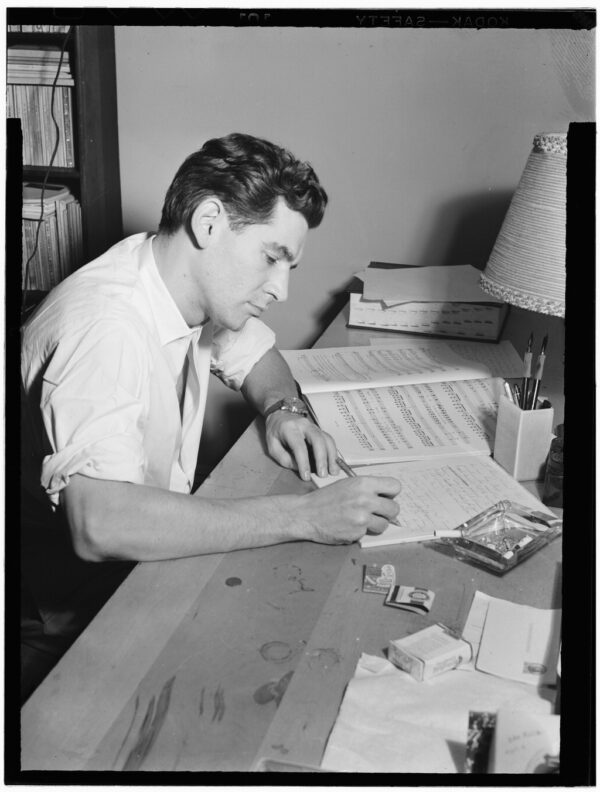

In 1949, the great choreographer Jerome Robbins approached composer Leonard Bernstein with an idea: How about updating “Romeo and Juliet,” replacing Shakespeare’s feuding families with Jewish and Italian gangs in the slums of New York? y could call it “East Side Story.”

“Prejudice will be the theme of the new work,” Bernstein explained, but he and Robbins were too busy. project was shelved, according to Humphrey Burton’s “Bernstein.”

A few years later Bernstein and playwright Arthur Laurents revived the idea, changing the setting to a different part of town (hence “West Side Story”) plagued by a turf war between two teenage gangs: the native-born Jets and the Sharks, immigrants from Puerto Rico.

Shakespeare’s Juliet became Maria, a girl who defies her overprotective brother, Bernardo, leader of the Sharks, by falling in love with Tony, who, after founding the Jets, left the gang to get his life together.

With a “rumble” looming, Tony’s buddy Riff tries to lure him back into the fight against the Sharks, while Bernardo’s feisty girlfriend Anita is torn between her love for him and her loyalty to her best friend, Maria. This tangle of alliances triggers a show-down that leaves three dead—murders as heartbreakingly pointless as the hundreds committed every year by today’s more lethal, more heavily-armed ”gangstas.”

Robbins was signed to direct and choreograph. Bernstein planned to write music and lyrics, but as usual ran out of time, so 25 year-old prodigy Stephen Sondheim was hired to help out. He acquitted himself so well, Bernstein ended up giving him sole credit for the lyrics.

show’s gestation was rocky, even for Broadway. When the producer quit six weeks before rehearsals started, theater gossips looked forward to a memorable disaster. Who would want to see a musical about prejudice which included several deaths and an attempted rape? But the talented team pressed on, discovering that Shakespeare’s tale fit surprisingly well into its new setting.

Leonard Bernstein Contributes

In the 1950s, Bernstein seemed to be everywhere: conducting orchestras, writing symphonies, teaching young musicians, scoring movies (notably Elia Kazan’s masterpiece, “On Waterfront”,) while dashing off two Broadway hits (“On Town” and “Wonderful Town”), an operetta (“Candide”), a modernist opera and a book. Bernstein even conquered television with his “Omnibus” lectures and “Young People’s Concerts,” as Burton explains. Even today, issued on DVD, these programs are a delightful way to introduce children and adults to the wonders of classical music.

Although Bernstein often composed in the highbrow, dissonant styles favored by mid-century musicologists, in “West Side Story” he supercharged his modernism with straightforward emotion. result was a torrent of passion and yearning that flowed directly from his heart into the hearts of listeners.

For all its grit and tragedy, “West Side Story” is the most romantic American musical. soaring lyricism of songs like “Maria” and “Tonight” tempers the dark themes of hatred and violence, creating a whole much greater than the sum of its parts.

Other Assets

But the other parts were great, too. Sondheim’s lyrics for his first Broadway show were so inspired and true to character that even he would never top them. Laurents’s taut, suspenseful book actually improved on Shakespeare in places, and Robbins’s dynamic choreography amazed.

Opening on Broadway in 1957, the show was well-reviewed and fairly successful, but it took the 1961 movie to make “West Side Story” the beloved classic it is today. director was Robbins, but his obsessive perfectionism put the film behind schedule and over-budget, so he was replaced by the dependable Robert Wise (“ Sound of Music”).

Natalie Wood, the star, was led to believe she would sing Maria’s songs, but her decent if limited soprano wasn’t up to the score’s near-operatic demands, so producers had the great ghost-singer Marni Nixon dub her. (Nixon also did the singing, unbilled, for Deborah Kerr in “ King And I” and Audrey Hepburn in “My Fair Lady.)

Wise’s movie won ten Oscars and remains one of Hollywood’s finest achievements.

Cast Can Sing and Dance

Now, exactly 60 years later, comes Steven Spielberg’s take. Avoiding the regrettable modern practice of casting A-list actors who can’t sing or dance in musical films (“Sweeney Todd”, “Mamma Mia”), this one wisely uses young, lesser-known performers who can do it all without being dubbed.

Ansel Elgort (what a name!) is a better Tony than Wise’s Richard Beymer, and he does his own singing. Mike Faist and David Alvarez shine as adversaries Riff and Bernardo.

Rita Moreno, the perfect Anita in 1961, returns at age 89 to play the kindly shop owner who tries to make peace between the gangs. Her hushed delivery of “Somewhere” is touchingly effective. Anita this time is Ariana DeBose, a fine singer whose fiery dancing almost gives off sparks.

entire cast is excellent, but I’ve saved newcomer Rachel Zegler for last. She’s everything Maria should be—lovely, innocent, proud, determined, and finally consumed with grief and rage. As if that weren’t enough, her exquisite singing gives Marni Nixon a run for her money. Remember the name—she’s going places.

Screenwriter Tony Kushner gives each character its due and its humanity, even the cops, who are actually portrayed more sympathetically than in the 1961 film. Sometimes characters speak a little Spanish (a touch not in the original) but not enough to confuse viewers who don’t. When they do, Anita reminds them: “Speak English! We have to practice!”

Gustavo Dudamel and the New York Philharmonic more than do justice to Bernstein’s immortal score, Justin Peck’s choreography channels Robbins, adding a few new moves, but above all this is Spielberg’s show. His camera swoops and glides, always in service to the story, and he finds exciting new ways to stage the iconic balcony scene and the dance at the gym.

So much could have gone wrong, but almost nothing did. few missteps are minor. “Cool,” sung by Tony to his crew, can’t touch the thrilling explosion Robbins made of it in 1961. And the pace flags near the end where it should accelerate, as it does in Wise’s version.

Will this new “West Side Story” replace the 1961 classic? No, but it can stand proudly by its side. We can stop cringing now and start thanking Spielberg and company for bringing this masterpiece to life again for a new generation, with deep feeling and phenomenal skill.

Pezou : American Treasures: ‘West Side Story’